I preached this sermon on June 6, 2021 at Trinity Episcopal Church, Fort Wayne. The primary text cited is Genesis 3:8-15.

I remember once when I was a little boy, I got into an argument with my dad. I don’t really recall what it was about, probably something unimportant. I just remember that in the middle of the argument, I ran out the back door into the yard and hid in some bushes. I guess I just wanted a quiet place to sulk and cry a little bit by myself.

But then my dad came out, looking for me, and the thing that I recall most clearly as I hid under the leaves, a little ball of fury, was the catch in his voice, a note of sadness and worry, as he called out my name, trying to find me. So I got over myself and crawled out, covered in dirt, and said, “here I am,” and he just looked at me, relieved, and said, “come inside.” And I did.

What a blessing it is, in our lives, to experience the kind of love that seeks us out and doesn’t abandon us to ourselves; the kind of love that sees past the fears and the frustrations of our petty, wounded hearts, the kind of love that looks at us unflinchingly and simply says, “it’s been a long day; come back inside.”

I hope and pray that you have known and continue to know that kind of love in your life, whether from a parent, another family member, a partner, or a friend. I hope and I pray that that’s the sort of persistent, active, reconciling love we are practicing in our common life here at Trinity.

And I also hope that this is the sort of love that informs our understanding of today’s reading from Genesis 3, that pivotal moment when Adam and Eve are, themselves, hiding in the bushes after that fateful, perilous bite of ripened fruit.

“They heard the sound of the Lord God walking in the garden at the time of the evening breeze, and the man and his wife hid themselves from the presence of the Lord God among the trees of the garden. But the Lord God called to the man and said to him, “Where are you?”

Where are you? In those three words, I think we can learn everything we need to know about God’s disposition towards us, from that moment in Eden until this very day, wandering the solitary paths of paradise, searching for his children’s faces.

Where are you? We have been formed in many different understandings of the nature of God’s love, but I hope, when you hear that question, you can hear, not the threatening yell of a vengeful authority figure, but that of a loving parent, that note of sadness and worry, the voice of one who knows that, yes, something has gone terribly wrong but is nonetheless fervently seeking you out, seeking a way to save you, looking for you in every shadowy corner, under every weeping branch where you might be cowering, seeking you and refusing to abandon you to the despair of your hiding place.

Where are you? It is the question God has been asking every day since that breezy evening in Eden, since that point in time, for reasons we may never fully understand, when it became possible for us to estrange ourselves from God’s loving embrace. It is the question that underlies the record all of God’s fierce and wild emotions in the Old Testament—

God’s grief and rage over Israel’s waywardness—where are you?

God’s sense of betrayal over humanity’s failure to embody justice, mercy, and peace—where are you?

God’s heartbreak as bow down before the work of our own hands instead of Divine majesty, trembling under the weight of our own fears, all while our One True Love continues to call out—where are you? Where are you? Where are you?

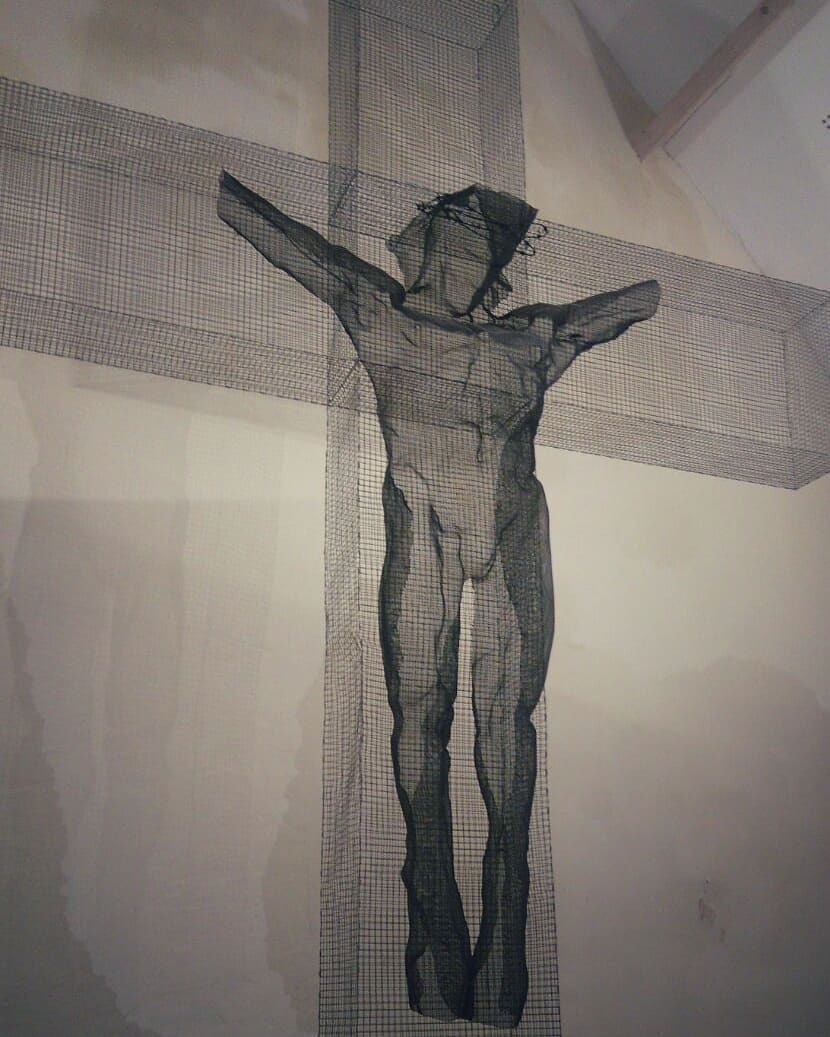

It is also the question that Jesus came to ask us, face to face: little children, my mother, my sisters, my brothers, I see you now with my own eyes, and you see me, but where are you, in your deepest heart? Do you even know? Do you remember where you belong?

And still, God is asking us that question. Still, God is waiting for us to reveal ourselves, to step forward and to offer the response that Adam and Eve never quite could, the response that a true relationship requires. The word for that response, in Biblical Hebrew is hineini.

Hineini. Here I am.

So much depends on us responding to this love that seeks us out, this love that calls to us in the cool evening breeze even as we keep hiding, even as the evening shadows fall down around us.

Everything that can be good and true in this fractured world depends upon us saying, as Abraham and Moses and Mary all did: Here I am.

Here I am, God. Covered with dirt and leaves and tears, my best intentions gone awry, my understanding limited, my heart a little bit broken, but here I am, God. I can’t promise to be perfect, but here I am. I am afraid, God, sometimes too afraid to speak, but here I am.

I wonder what it would look like if we could each step out from our hiding places, the ones we’ve run to, the ones we’ve built up around ourselves, and step a little bit closer to one another, a little bit closer to that place where God stretches a hand out to us in the twilight, and I wonder if we might let that question and that answer, that call and response, guide the shape our lives.

What if we said each day, Where are you?

Where are you present in my life, God? And where is my neighbor, where is the stranger I forgot to welcome, where is the enemy whom I was taught to fear? Where is the deep, tender heart of the blessed earth, where is the hidden paradise, the love hidden in plain sight? How do I press my soul down into its embrace? Where are you?

And what if we also said each day, Here I am. Here I am, Lord. Here is my face, seeking your face. Here is my voice, speaking your unutterable name on my breath. Here is my body, and here is my mind, and here is my heart; may your Spirit mold them into vessels of your love. You don’t have to search or grieve for me any longer. Hineini. Here I am.

Where are you?

Here I am.

Perhaps this small conversation is the one God has been waiting to have with us for our entire life. Perhaps all God ever wanted was to find us, to bring us home, not back to the beginning, not back to Eden, for we know too much now, we are grown now, but back to our true home, which is within God’s very own heart.

You don’t have to hide from God anymore. We never truly did.

God is calling to you, and there isn’t anything to be afraid of now.

So get up.

And say, “Here I am.”

And come inside.