I preached this sermon on Sunday, August 17, 2025 at St. Anne Episcopal Church, West Chester, OH. The lectionary text cited is Luke 12:49-56, which includes the following:

Jesus said, “I came to bring fire to the earth, and how I wish it were already kindled! I have a baptism with which to be baptized, and what stress I am under until it is completed! Do you think that I have come to bring peace to the earth? No, I tell you, but rather division!

Jesus has something to say today, doesn’t he? All this fiery language and talk of division. If you were looking for a feel-good Gospel passage today, my apologies, but I want us to really look at this notion of division rather than scuttle past it. Because I’ll tell you something, I love Scary Jesus. Really, I do!

Not because I take what he says lightly, but because Scary Jesus—or perhaps more accurately, Prophetic Jesus, No-Nonsense Jesus—is willing to say and do the hard things that love and truth require. He is willing to take a stand for what is good and willing to name what is not.

This is the sort of division that he brings—it’s not about enmity, but clarity. The clarity of telling the sheep from the goats and the wheat from the chaff in our hearts and in our world. Jesus is here to give us clarity about what is worth holding onto through the long onslaught of the years. And what must be let go of.

When I think of this sort of division, I am reminded of a certain legendary incident in my family.

My grandparents, you see, had very different philosophies about how many old items in the house should be held onto. My grandma believed strongly that she might need to look at that stack of TV guides from the 1970s and, as you know from prior sermons, she had an epic collection of empty Cool Whip containers just in case. My grandpa, on the other hand, was a fitful organizer. He was occasionally seized with passionate zeal for empty countertops and cleared-out corners. And on one such occasion, he went nuclear.

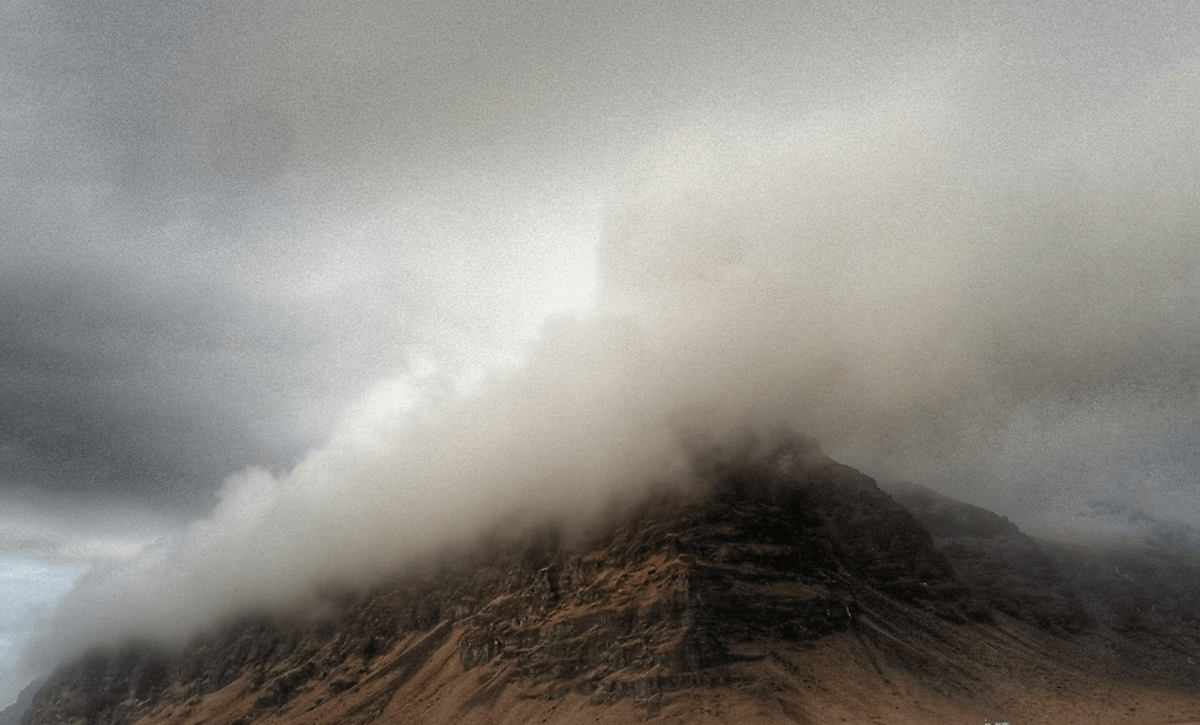

Their attic was a place where no person dared tread; the detritus of decades was accumulated there—old photo albums, broken toys, enough boxes of papers to rival the Library of Congress. And one day, my grandpa must have been seized by a vision of cleanliness, and he just snapped. He had that baptism of fire burning him up inside. So he stole up the ladder to that attic and before we knew it, he had pried open the little window and was tossing bags of old clothes and God knows what else down onto the front lawn for all the neighbors to see!

You want to talk about households divided. Hell hath no fury like Verna Hooper on that day; she was up that ladder fast as a squirrel and a whole lot louder than one. Even Scary Jesus would have been scared. I won’t bore you with the gory details, but let’s just say every single item went back up into the attic and my grandfather learned afresh the meaning of marital penitence.

I would venture to say, though, that neither of them was fully in the right. I get my grandpa’s point: when we are frustrated by the weight and mess of the world, it is indeed tempting to think we should just toss it all out and start over. Send in the cleansing flood, or break down the walls of the spoiled vineyard, as Isaiah puts it today. Just let it all go.

But my grandma had a point too—there are things worth saving, even in the messiness. There are things that should be preserved, and there has to be someone willing to stand up for their value.

As is usually the case, the path of wisdom falls somewhere in the middle of these two postures. We have to figure out what to hold onto and what to let go of, and how to tell the difference. That’s the kind of division that Jesus is talking about. He is not interesting in starting fights among families for no good reason. But he does need the human family—all of us, together—to really get clear about what matters and what doesn’t. Have we figured it out yet? Maybe we’re still working on that. I hope we are.

Because that work of division, friends, that laborious and slow discernment between heirloom and junk, that is what the church is asked to do in each age. Informed by study, shaped by community, emboldened by love, empowered by the Spirit, we have to decide as best we can what stays and what goes. What is the substance of God’s mission and what is just clutter. And we do that, hopefully, for ourselves and one another here, and then we step out into the public square and declare the truth there, too.

And it’s funny, you know—I think The Episcopal Church is accused sometimes of being like my grandpa; that we, seized by some vision of inclusivity and love and social justice, have tossed out all of the fundamentals of the faith. This is absurd to me. As if, somehow, love and inclusivity and justice were not themselves the exact fundamentals that God is always interested in. I’ve read the Bible, thank you very much, and God does indeed care about those things deeply. Come to think of it, maybe we are the fundamentalists after all!

In truth we have not been seized by misguided zeal; but nor are we like my grandma that day, digging in our heels, holding onto the past. Instead we have been doing the long, careful, imperfect labor of figuring out what stays and what goes in the unfolding emergence of God’s kingdom. We are still doing it. We will always be doing it. Debating Scripture and structure. Cherishing our hymns and collects like Cool whip containers that are enduringly useful. And letting go of some of those old prejudices and fears, like TV guides that have nothing helpful to show us.

We do all of this, by the way, not because we are “getting political” but because we are faithful to the God who is still speaking into the present moment. We hear the message of the Lord and we take it seriously. We hear Jesus, who says I have not come to bring mere peace—I have not come to bring a passive acceptance of the deadening forces of this world. No, I have come to bring an ever-renewed capacity for division between right and wrong, I have come to bring clarity and awareness. I have come to empower a choice between what is true and what is a lie. So follow me, he says, follow me with love as our guide, and find out which is which, and let’s learn to speak it out loud.

How urgently we need to follow him now, this truth-telling, fundamentally loving and unafraid Jesus. How urgently we need to tell the world who he actually is, and not what he has been made out to be by the transactional exigencies of partisanship, culture, and power.

Because Scary Jesus, Prophetic Jesus, No Nonsense Jesus, the Jesus that I fear and love and follow, has never changed his message. He has never submitted to the lies of any age. And he never will.

Today we hear his rejection of a cheap comfort at the expense of truth. We hear his dedication to separating out what is worthy and good from what is destructive to the human spirit, and we see his willingness to die and rise again for the sake of this gentle and hospitable Kingdom. A Kingdom where all are welcomed at the table. That is what Jesus is about. That is who Jesus is.

And if that is somehow offensive to the prevailing and popular order of things—GOOD. If that is divisive—GOOD. I would rather stand in the divisiveness of an unequivocal love for all people; I would rather pay the price for that divisiveness; I would rather pursue its invitation to the edge of comfort and respectability, just like Jesus did, than live in uneasy peace with the world as it is.

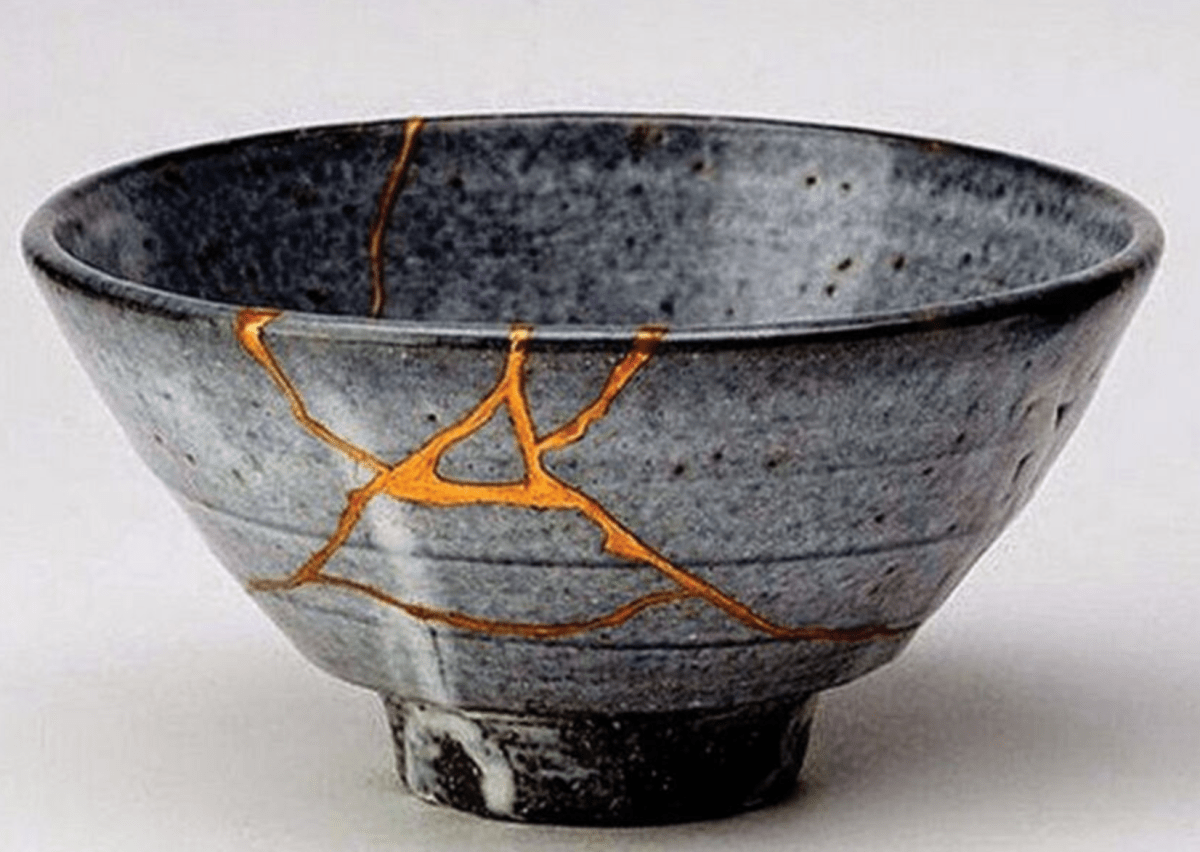

I would rather the institutional church die singing songs of love than live for something other than the real Jesus. I would rather be mocked and misunderstood for doing the long, hard, foolish, communal work of sifting through the brokenness and the beauty of life and crafting a future out of it, together. Us and God, together. It’s not easy or efficient, but that’s the only kind of church I want to be.

So what kind of church are we going to be, my friends?

Maybe, with God’s help, the kind that is able to do some division.

And wouldn’t you know, as it happens, that is also exactly what occurred eventually with my grandparent’s house, long after the attic incident.

Once they were both gone, my family members carefully went through every room determining what to let go and what to hold onto. It was hard, and it was grief, and it was love, and it was the resurgence of a million precious memories. I think the clothes and the TV guides did go away; sorry Grandma. But not everything. Some things, like that old organ in my office, and like the Cool Whip containers that show up in my sermons, some things endure, undaunted by the years.

And that was, in the end, the necessary division—the healthy, holy division—which made what really matters so very clear to us.

That is the work we must all do eventually. And it is the work of the church, too.

So, if we are feeling brave, let’s go up to the attic, and sit down amid all the boxes of memory, and regret, and fear, and hope. Let’s speak of what is true, and admit what never was.

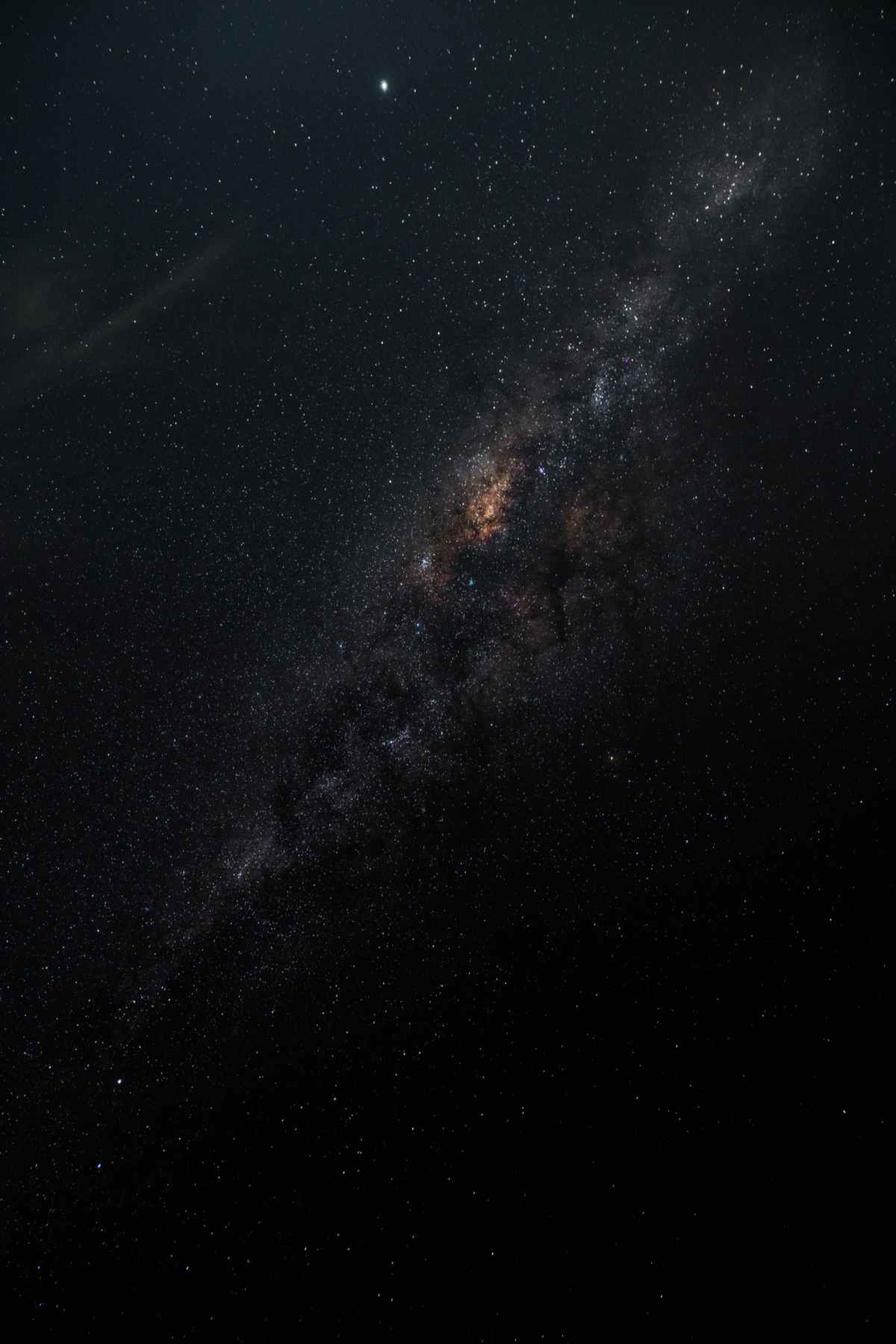

Let’s hold it all up to the light—and sort through—and do the work the Lord has given us to do.