I preached this sermon on Trinity Sunday, June 12, 2022 at Trinity Episcopal Church, Fort Wayne, IN. The lectionary text cited is John 16:12-15.

Ever since I was a little kid, I have loved looking at maps. Our family went on lots of road trips, and there was a sort of weighty, sacred significance in the big printed road atlas that was usually kept somewhere in the car. Even if we weren’t going anywhere in particular, we would get it out and we would look at it together, and I would trace my finger along the blue and red and green roads and highways crisscrossing the printed page like ribbons, or rivers, or veins, each one an invitation, a daydream, a path leading somewhere, towards a place just over the horizon of the present moment. A place that, to my young mind, was mysterious. A place that was beautiful.

To this day I still love looking at maps and pondering places to explore, both near and far. And so it happened that this weekend I was scrolling on my phone across the map of this area and I noticed the place, about an hour from here, where the state lines of Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan converge. As best I could tell, it was just a spot along a country road pretty far from anything, with a little stone marker. Worth driving an hour each way? I’ll let you be the judge of that, but the map was calling out to me, and so I hopped in my car on an impulse and headed north.

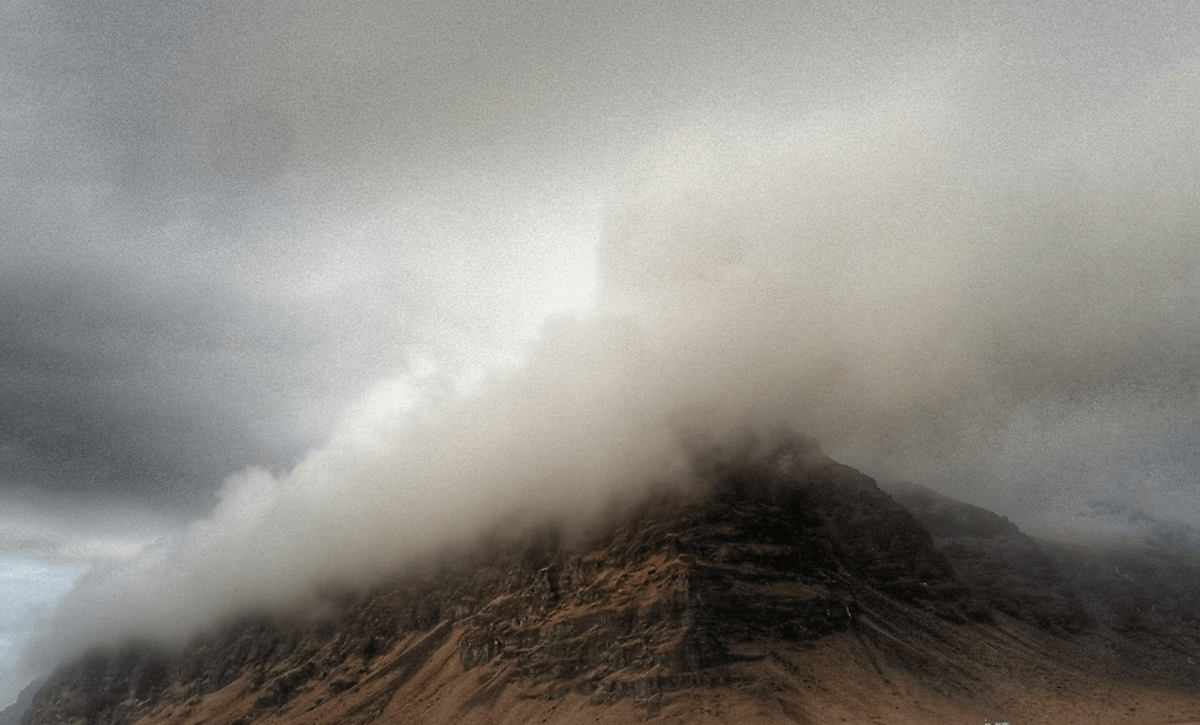

After getting off of the interstate, I ended up on one of those beautiful two-lane country roads that we have in abundance around here. The land rose and fell gently, like the belly of a sleeping giant. The clouds were big and voluptuous, the trees an insistent shade of green, the red barns and the farmhouses nestled among the fields. And still I kept driving, and driving some more, far past any town, out to where the roads arent quite yet dirt, but where they’re starting to think about becoming dirt.

And suddenly, there it was. Just off the road, with a little place to pull off: a stone marker perched on a small rise, which indicated that 130 feet to the south, the three states meet in one spot. And so I parked the car and walked a little ways, and there it was—not much to see, I’ll admit—just a little metal plaque embedded into the middle of the road with the letter “M.” So I’m guessing Michigan got to put it there.

And as you do when you drive over an hour to see a letter in the middle of the road…I stood on it. And then I took a couple of pictures of my feet standing on it. And I looked around at the loveliness of that quiet road, accompanied only by the birds and the breeze rustling the flowers and the wild grass, and I thought about how strange and yet oddly thrilling it was to be standing upon the precise intersection of three places, each with their own unique character, each with their own people and histories and hopes, and yet here, together, gently resting up against one another, hidden away in the middle of nowhere, or, depending on how you look at it, in the middle of everywhere.

And while it was not quite as glamorous as some of the places on the map I’d daydreamed about as a kid, it was mysterious. And it was beautiful.

Now, given that today is Trinity Sunday, that day in the Church year when we preachers try, however imperfectly, to ponder and speak about the God revealed to us in Scripture who is both three and one, you might already see where my imagination is going with this. And although I admit any attempt to reduce the Trinity to a tidy analogy or image is destined to be insufficient, I couldn’t help but think about it as I stood on that spot in the road, trying to imagine where exactly on that little plaque one state ended and the other started, searching for the infinite vanishing point between uniqueness and unity.

Uniqueness and unity. We could say something similar about the Triune God, a theological mystery which is itself perhaps marked with an M, somewhere out beyond the cosmos, in the backroads of heaven, among the fields of wheat and the wildflowers and the swooping doves. Theologians and preachers and all kinds of other people have written a lot of words trying to map the Trinity, to describe its contours and characteristics and the best way for us mere mortals to approach it. We all want to “get it” or get close to it. And yet as close as we might get, we can never quite reach the center of what or where or how the Trinity is. It is hidden from us, just out of reach, that infinite vanishing point where Father, Son and Spirit touch and intertwine, beyond the limited scope of our perception. It is nowhere, and it is everywhere. It is mysterious. And it is beautiful.

How thrilling and humbling it is, when you really think about it, that as Christians we give our lives, our whole selves, over to something—to Someone—whom we can’t quite understand. But that’s what love is, in the end, isn’t it? A headlong leap into mystery.

And so today, on Trinity Sunday, we honor that mystery of God’s love, not trying to solve it like a riddle or simplify it into a diagram, but instead to celebrate the journey that we make together in its general direction, like travelers with a map in our hands—longing for the promise that lies beyond the horizon of the present moment, searching for that place at the end of the long road, the place where all of our unique stories, all of our hopes and our homelands meet, gently resting up against one another— a place we know is real because Jesus has revealed its possibility to us, even if we can’t quite describe it or see it yet.

But that’s the whole point—we haven’t fully arrived. We haven’t plotted the precise coordinates of the Kingdom—no, not a single one of us. And we as the Church are at our best when we acknowledge that our journey toward understanding God is still a work in progress. The depth of the Trinity, that is to say the depth of God’s grace-filled self, is still being revealed to us. And admitting this prevents us from all manner of ills: legalism and self-satisfaction and complacency and hardened certainties. It keeps us tender, open to being surprised, open to admitting that perhaps God is even more wondrous, more loving, more liberating than we—or anyone—has ever dared to hope.

“I still have many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now,” Jesus says in today’s Gospel passage. “When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth…he will declare to you the things that are to come.”

This story—this revelation of the divine life of the Trinity—is not over yet. The Spirit is still working within us and within the present moment; the Son is still journeying with us, even to the end of the age; and the Father stills waits to greet us, his prodigal children, at the end of our travels, running across the field, arms open wide, a feast heavy upon the table. The Trinity is all of this, and more. It is mysterious, and it is beautiful.

Our only task is to keep going. Keep going, even when we stumble. Keep going, even when it feels like we’ve lost the path. Keep going, even when nobody else seems to want to come with us. Keep going, even when the map is stained with our tears and the lines bleed together. Keep going.

Because if nothing else, to speak of the Trinity, the way it moves and holds and calls us, is to speak of God’s ongoing invitation to keep going. It is the proclamation that God was, and God is, and God will be with us as we do so, and that wherever we are going, we will meet him in the end. We will converge, somewhere on that hidden road, into that infinite vanishing point of uniqueness and unity, of God and of creation, of flesh and blood and bread and wine and breath and wind and flame. We will stand right there at the intersection of eternity, and finally, we will know. Finally, we will be known.

I still keep an atlas in my car, by the way. Every once in a while I’ll take it out and trace the roads on the map with my finger, dreaming of what more there is to see. There’s always more to see. The only difference is that now, I have come to know that you don’t have to travel very far to see wondrous things. The infinite mysteries of the universe—of love, of life, of God—are close to you, closer than you can imagine.

Sometimes, if you know how and where to look, they’re just under your feet.