I preached this sermon on Sunday, July 20, 2025 at St. Anne Episcopal Church, West Chester, OH. The lectionary text cited is Luke 10:38-42.

Not too long before I began my training to be a priest, I had a meeting with my rector and mentor, Fr. Shannon. I was, as you might imagine, a bundle of nerves and excitement and anticipation, wondering what on earth I’d gotten myself into, even though I also knew it was the only thing I could imagine doing with my life.

Fr. Shannon was and is a prayerful and wise man; he is the sort of person who cuts right to the heart of the matter when you speak with him. Even so, when I asked him for any last-minute advice as I headed off to seminary, I wasn’t quite prepared for the simplicity of his words.

Just keep your eyes on Jesus, he said. Just keep your eyes on Jesus and you’ll be fine.

That was it.

Now, I can be an over-thinker. With good PR one might call my personality type “introspective,” but if we’re honest, sometimes I just get in my head about stuff.

So when I’m all worked up inside about the future and Fr. Shannon just says to me, keep your eyes on Jesus, I will admit to you that internally, I was kind of like, uh huh….and??? Throw me a bone here, Father. There’s gotta be something more to it than that. How am I going to crack the code and become the ideal priest? How am I going to help fix all the problems of the church and the world? How am I going to shoulder the impossibility of the task ahead?

But that was all he said that day. Keep your eyes on Jesus.

So I packed my Uhaul truck with a lot of unanswered questions and went on my way.

And wouldn’t you know, that he was exactly right? Because I would learn in all sorts of ways throughout my years of training and formation—and I continue to learn—that keeping your eyes on Jesus is a deceptively simple invitation. It is actually really, really hard, especially once we realize how many other things we’re accustomed to focusing on.

The truth is our complicated lives and the complicated world around us and our egos and sometimes even the ups and downs of Church itself seem to conspire to keep our eyes on anything other than Jesus. Anything other than the simple, devastating truth of him and all that he offers, teaches, and dismantles.

I got to seminary and, as with anything, it was so easy to get caught up in the externalities of it—the grades and the institutional anxieties and the questions about the future. So easy to forget, if I wasn’t careful, that none of that stuff mattered if I wasn’t first focused on the deep, healing love that I had found in Jesus.

And as with any great love, some years on, I’m still only beginning to discover its fullness—only beginning to see what it means to keep my eyes on Jesus and to let that seeing change me.

I tell you this story, though, because in this light, I hope we can reassess today’s gospel passage. Here’s another confession: if I hear one more take on this story that divides us all into “Martha” types and “Mary” types, or that pits action against contemplation, I will pull out the nonexistent hairs on my head. With all due respect to those interpretations, this is not a passage about any of that. You are not just a Martha or a Mary. This is a meaningless distinction.

If you need some convincing on this point, consider: was Jesus a Martha or a Mary? Was he an active or a contemplative? The answer of, course, is that he was all of these things together and none of them alone. He was and is the unity of love and action, of prayer and prophetic witness, of service and surrender. Which is why, of course, we are supposed to keep our eyes on him—so that we might become like him.

Consider, too, that in Scripture Martha and Mary are both more than this isolated passage would suggest. Martha, in John’s Gospel, is not a hapless busybody, but a person of deep faith and insight: she is the first person in that book to proclaim Jesus as the Messiah. And Mary, in that same Gospel, is no retiring navel gazer, but a person of decisive word and action. She pours out her expensive ointment and anoints Jesus’ feet with her hair, defying criticism and convention.

Imagine that, women in scripture actually being more complex and powerful than church interpretive tradition has allowed them to be? What a concept! So let’s lay down that tired old binary these women supposedly represent. It is not real.

The point here, instead—the distinction that Jesus is making when he talks about Mary “choosing the better part”—is a question of where our focus lies. It is his gentle, direct reminder to Martha to keep her eyes on him in all that she does. In the things that she can set into order and in the things that remain a mess—in all of it, he wants her to not forget what it’s all for, what it’s all about, what it’s all moving towards: union with him, life in him, the eternal love affair between God and creation consummated in him.

Because Martha, worried and distracted by the many things she genuinely cares about, can only truly learn how to love them if she keeps her eyes on Jesus and receives him not just into her home but into the very depths of her soul.

And the same is true for us, friends.

All that we do in the church—our programs and our fellowship and our formation and our service projects—all of it is meaningless unless we first keep our eyes on Jesus and receive him into the deepest parts of ourselves. You’d think this would be obvious, but just like that advice Fr. Shannon gave me, it is deceptive in its simplicity.

Because it is so, so easy to become distracted, worried, and tempted by many other things—the ups and downs of economics and politics, the personal hurts and hungers that plague us, the unresolved conflicts and the institutional inertia. They are all important in their own way; they all need some faithful tending. But without keeping our eyes on Jesus—without making him the main thing that we are actually about—we will never go beyond a sort of well-meaning crisis mode. And I think we find ourselves in well-meaning crisis mode a lot of the time.

But God wants something more for you than that, St. Anne. God wants your liberation. God wants your peace. God wants you to be able to breathe again. And to help others do the same.

And the journey towards that liberation and peace and room to breathe begins, and becomes, and ends, for us, in focusing on Jesus. Listening to him, praying as he prayed, confessing to and confiding in him, studying his teachings, modeling our social ethics and our relationships upon his generous and gentle love. And then receiving him—reaching out our hands and receiving him into the deepest parts of ourselves.

This is what we must be about here at St. Anne, first and foremost: keeping our eyes on Jesus. And when I say Jesus, I mean the real Jesus, by the way, in case you’d forgotten or never been told what he’s actually like: living and present, responsive to reality, no enemy of science or truth or human experience, sacramentally available, still-being-revealed to us, Spirit-driven, justice-seeking, reconciliation-making, mercy-rendering. That is Jesus. Keep your eyes on him.

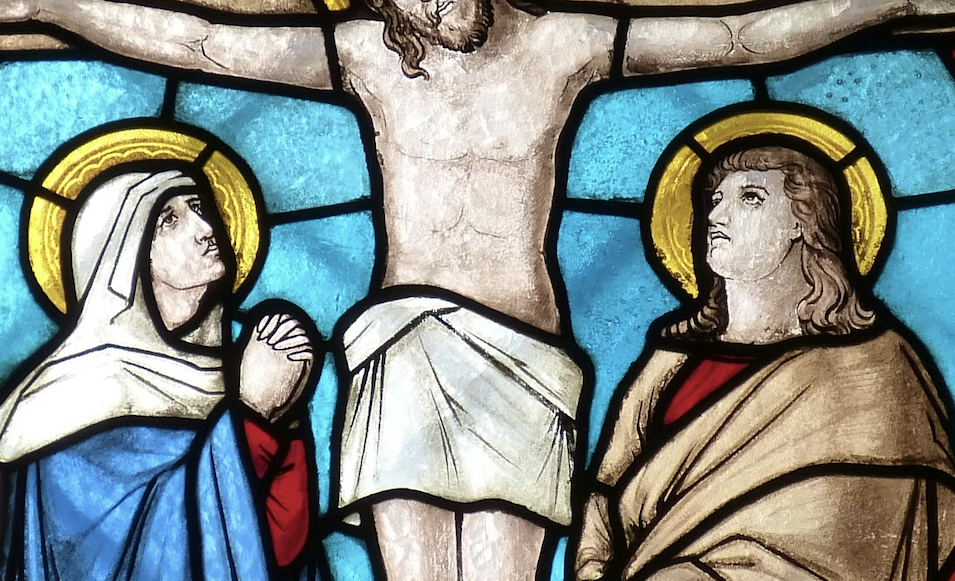

The stranger-caring, everyone-welcoming, difference-respecting, listening, peacemaking, table-turning, mountain praying, active, contemplative, holy Jesus. The Martha and the Mary and the Peter and the Paul and even the Judas-loving Jesus. Keep your eyes on him, because he is there waiting to love you, too.

Not Christian nationalist Jesus; not conservative or liberal Jesus; not idol of patriarchy Jesus; not disembodied, benign, relative-truth Jesus; not war-monger Jesus; not mere symbol Jesus; but the real, risen, living, loving, bleeding, blessing, breaking, laughing, dancing, fire and firmament Jesus who demands nothing less than all of you and nothing more than this: to see him, and to fall in love with him, and to fall in love with your neighbor and the world again because of him, and to die and to live again, all at once in him.

That’s who I am going to keep my eyes on, no matter what else comes along.

Just like Martha, and just like Mary, and just like everyone else who has ever dared to look up from the worries and distractions that surround them and instead chooses the better part that is, quite simply, Jesus. That is, quite simply, love.

Whatever else we do, lets start there. Just keep our eyes on Jesus.

As a wise friend told me once, do that, and we’ll be just fine.