I preached this sermon on August 27, 2023 at Saint Anne Episcopal Church, West Chester, OH. The lectionary texts cited are Exodus 1:8-2:10, Romans 12:1-8, and Matthew 16:13-20.

Some years ago, there was an essay published in the New York Times and it was tantalizingly titled, “To Fall in Love with Anyone, Do This.” Now, I admit that I was rather skeptical when I saw that title; it sounded like one of those ads you see on the internet, offering “one weird trick” to make you look ten years younger or to regain your lost hair. As you can see, I have not generally taken advantage of those ads.

But being single at the time, I was intrigued by the idea of a surefire method for finding love, so I read on. The author, Mandy Len Catron, described a study done in the 90s by psychologist Dr. Arthur Aron, which suggested that significant levels of connection between two people could be achieved very quickly by asking one another a series of 36 vulnerable questions over a 90 minute period. After asking all of the questions, according to the Times essay, you were then supposed to gaze into the eyes of the other person for *exactly* four minutes and…voila. Love.

If this sounds a bit far-fetched to you, I get it, though for the record, in both the original study and in the essay, some marriages did emerge from this initial moment of connection. So, hey, you never know. Dating is tough, you have to get creative.

But romance aside, it does make sense to me that there would be a unique sort of potency in the combination of knowing and seeing someone with great intentionality. So often, we only casually consider the people in proximity to us, even the ones we are around a great deal. We know their names, maybe some of their hobbies or associations, and their general appearance, but how often do we look, really look at them? How often do we seek to know, really know, something substantive about their inner life or their memories or their dreams? For that matter, how often do we strive to see and to know ourselves in that way?

It can be a little scary, if we’re honest, to know and to be known on that level. Maybe we fear that if someone actually sees us as we are, all of us, every mistake, every quirk, every wrinkle, we will become less lovable in their eyes. And maybe we fear if we see others in their fullness, we won’t know what to do with it, we won’t be up to the task of loving them in the way they need.

I’ve been on both sides of that equation. I think of the times when I have been hesitant to share my story and my identity with others for fear of rejection. And I think of the times, whether in my hurry or my hard-heartedness, that I haven’t looked into the eyes of that person seeking assistance on the street, my gaze downcast, hiding from them, hiding from our shared humanity. Maybe you’ve experienced these things as well: opportunities missed to be seen, to see, to experience the connection that only comes from open eyes and open hearts.

But we learn in Scripture time and time again that the flourishing, the healing, and the salvation that we seek can only be found when we dare to look and to be looked upon, in that space of mutual recognition, both with our neighbor and with God.

In our Exodus story, it is the willingness of the midwives to see the beauty and the humanity of the Hebrew children that gives them the courage to defy Pharaoh’s edict.

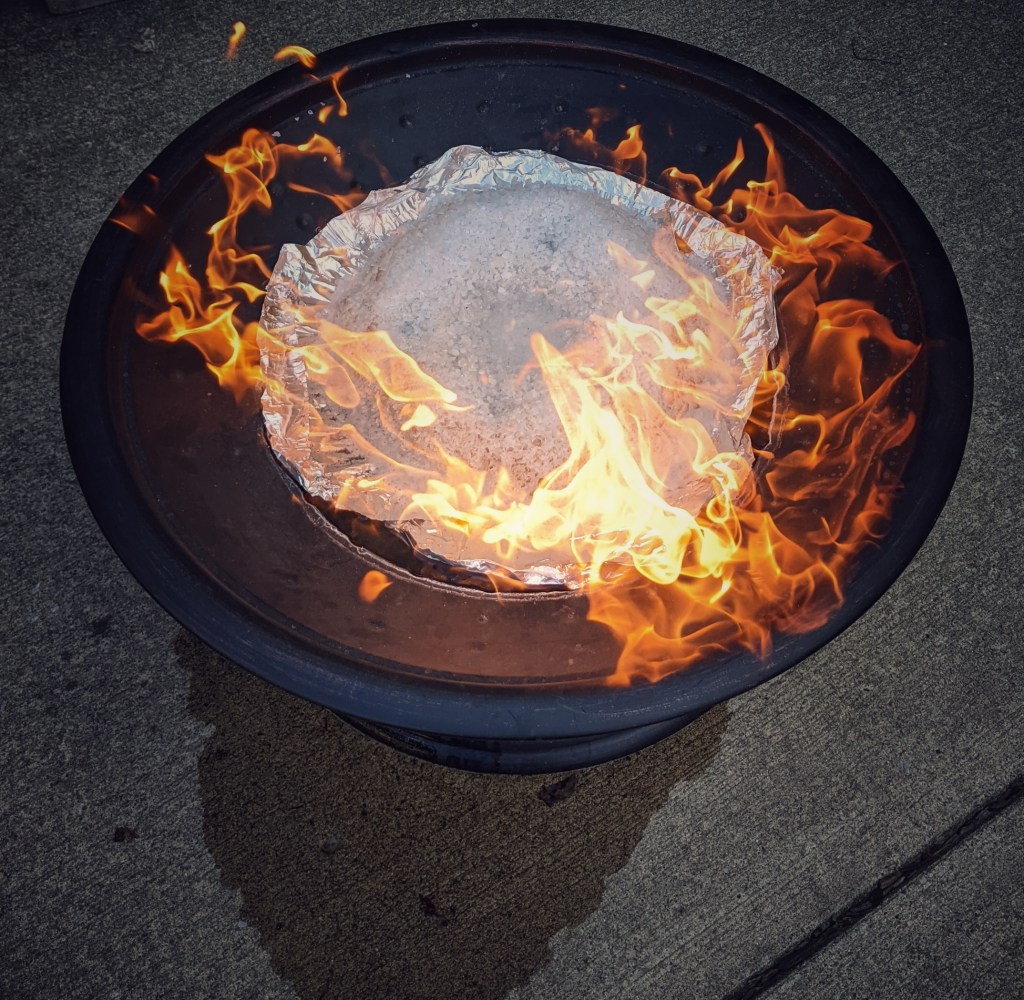

And St. Paul is encouraging a certain type of self-disclosure in the letter to the Romans when he invites the faithful to ‘present [their] bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God” offering up not just the parts of themselves that seem impressive or strong or unmarred, but the totality of themselves, their creaking bones and their broken hearts and their unanswered questions, to let all of it be placed upon the altar of life, where God in Christ will see it all, and hold it all, and render it all into something beautiful.

But part of the strange and lovely mystery of the gospel is that the work of seeing and being seen is not humanity’s alone. Because in Jesus, God’s own life is laid out for us to see, it is placed on the altar, too, that we might know him and render something beautiful from divine self-disclosure.

And so God stands before us with his own list of vulnerable questions, his own desire to look us in the eye for four minutes, or maybe forever, to give us a glimpse of his eternal longing for us.

This is what we encounter in today’s Gospel passage, in that all important question on Jesus’ lips, perhaps the most vulnerable question that God has ever asked of humanity: Who do you say that I am?

Who do you say that I am, my friends, my children, my infuriating and precious creation? Who do you say that I am, now that we are face to face? Am I another prophet? Am I another king? Am I a projection of your own desires? Am I an instrument of your political agendas? A benefactor to meet your needs? Or do you see, do you know, do you feel the way that it is much more than that, do you sense how heaven erupts in the space between us, the way that an undying love weaves in and out of every question I ask you and every story I share? Do you understand who I am and how far I have come in order that you might understand?

And if you understand, can you love me? Can you love me back, as I love you?

Who do you say that I am?

And Peter, on behalf of the other disciples, on behalf of all of us who would follow, says,

You are the Messiah. You are the Son of the Living God.

You are the One we’ve waited for. You are the Love of our Lives, you are the Love of Life itself. Yes, we understand.

And I like to think that Jesus smiles in that moment because at last God knows what it feels like to be seen.

If we want to know what heaven on earth can look like, how we might participate in it day by day, this moment is instructive. For if the God of the Universe came to be with us in the flesh, that we might see and know and name him as our own truest love, then perhaps our interactions with one another should reflect this.

Perhaps, on the most basic level, our discipleship begins simply by looking, really looking, into the eyes of the people we encounter—the familiar ones and the strangers, the friends and yes, even the enemies—especially the enemies—and saying, yes, I see you. I see you. At the very least I want to see you. And while I’m at it, let me show you something of myself, too, and maybe in that brief moment of vulnerability, when we behold each other, something new will begin to take root in each of us, something that feels a little bit like falling in love, even if only for a moment. It’s like one weird trick to change the world.

You might be wondering if I ever tried the experiment in that essay. Sort of. Matt and I have asked each other some of the questions, and they’re really good. The four minutes of eye contact still feels a little daunting to me.

But it has reminded me that one of the most fundamentally important things we can do, and one of the bravest, is simply to see what is, and to love what is, and to believe that we, too, are worthy of being seen and loved. Because if you look closely enough, no matter whom you meet, you will always be looking into the face of the Holy One, if you choose to recognize him.

Just like the essay said, to fall in love with anyone—or really, to fall in love with everyone—do this.