I offered this meditation at a service for The Longest Night at St. Anne Episcopal Church in West Chester, OH on December 20, 2023. It is a time of prayer, music, and stillness for those who are struggling in the holiday season.

God comes to us in the dark. This has always been true.

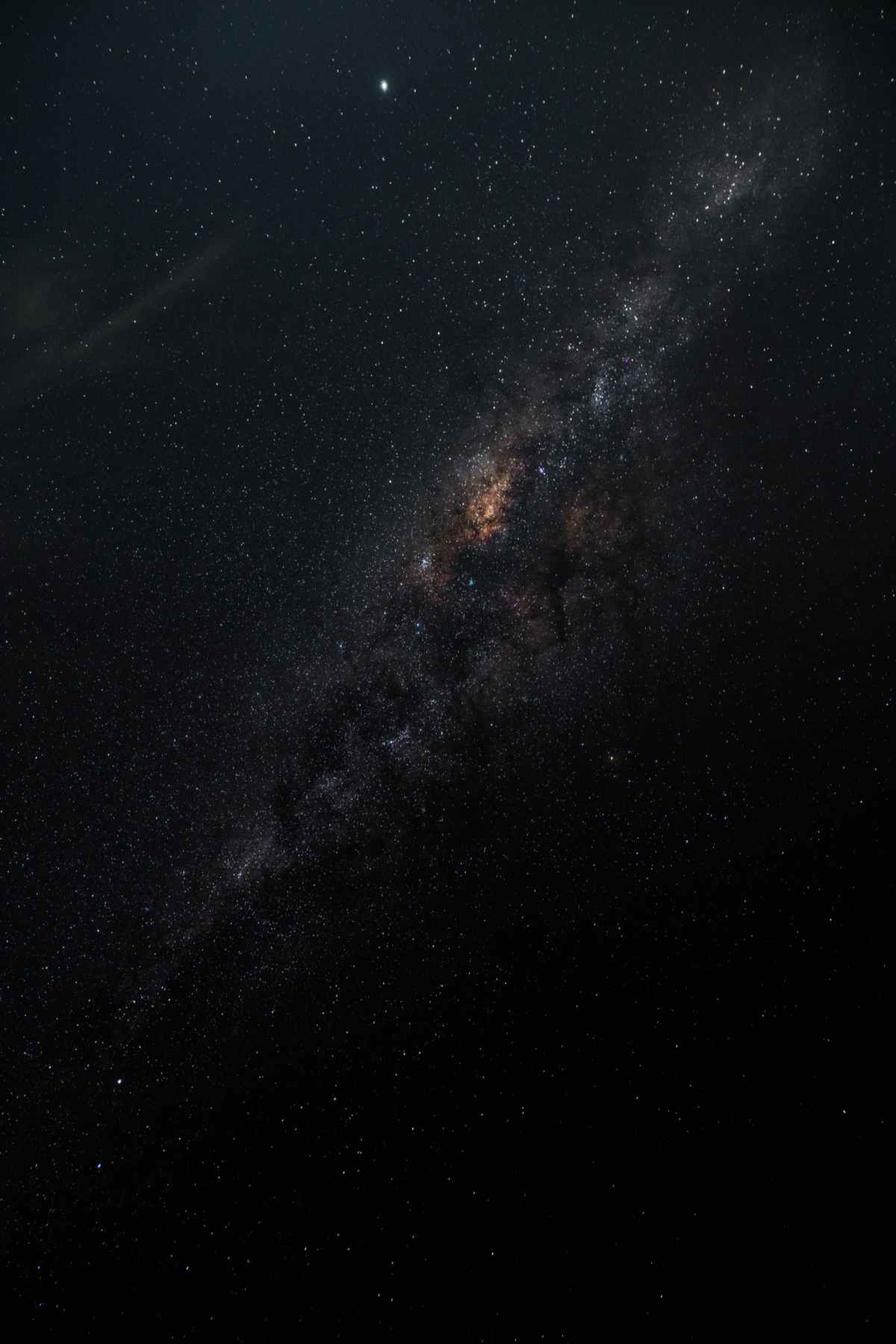

In the beginning, when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep. So says Genesis. So say our ancestors in faith, grasping back through time, back through the shadowy recesses of human memory, back to an original stillness, an original peace, an original fullness, back to when God, alone, was—and it was dark, and it was already good.

And all that follows—let there be light, and let there be all of this, and let there be you and me—all of it emanated from the darkness of love, where God dreamed and saw visions, where God composed the constellations, where God traced out the edges of the universe and imagined all that could be if there were such a thing as being. In the dark, God already knew both the price and the promise of being—what it would require—of God, and of us—and so God made a promise, from the very start, when our being came to be:

And that promise is: I am here. I am here. And again and again, when you lose sight of me, I will come to you. In every season, in every hour. When the light is bright, I am here. When it fades, I am here. And when it is night—on the face of the earth, or in the depths of your soul—then I am still here. You will not lose me in the dark. No, in the dark you will encounter me as I was from before the beginning: hidden but present, dreaming but awake, tracing, now, the edges of your face, your flesh now holding a universe of meaning. I am here, gazing at the constellations in your eyes, reminding you that being, simply being, here and now, together, is enough. It is all I ever wanted. It always has been. Even in the dark. Especially in the dark

For God comes to us in the dark. And this has always been true.

…

Despite this truth, we have a complicated history with the darkness, for reasons both pragmatic and imaginative. Job calls down the darkness as a curse; the Psalmist yearns for light like the watchmen waiting for morning. We understand this in our bones.

Because, until recently, the night was, for most people, an inevitable and somewhat threatening feature of daily life. Before electric lights and heaters, it was a cold and dim and dangerous time when one had to gather in close to others for safety and warmth. For our siblings who have no home to go to on this night, for those who are alone, this is still true—the night is not always our friend.

And yet there are other reasons we fear the dark, ways we have been formed to fear it in our mind’s eye. We have been taught, too often, that night metaphors are literal—that the light itself is somehow truer, purer, stronger, more moral, and that the darkness is a time of indolence, of deceit, of confusion and waywardness. And so when we find ourselves in a seemingly dark place—a place in our lives where we cannot see the path ahead, where we cannot understand what has happened to us and why—we might assume that we have been forsaken, that we have been forgotten, that we are at fault, or that God has left us to fend for ourselves.

We call this the dark night of the soul and think that we are talking about God’s absence. But we are wrong.

For we must remember, again: God comes to us in the dark.

Not just in the beginning, but always. The darkness is when God chooses to appear.

Consider how the Passover and the Exodus and God’s liberating work all began at night.

Consider God speaking to Moses on a mountain covered in thick, dark cloud, amid thunder and lightning.

Consider Jacob wrestling with an angel all through the night, claiming a blessing upon his wounded body before sunrise.

Consider the promise spoken by the prophet Isaiah: I will give you the treasures of darkness and riches hidden in secret places.

Consider the child, soon to be born in Bethlehem, in the silent, holy, starlit night.

Consider the Risen Christ, emerging from the darkness of the tomb into the predawn shadows of a garden.

And consider how the Lord promises his return when “the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light,” how he will reveal himself, in the end, as he was in the beginning, emanating from that deep original mystery, that unseen, unspoken, ageless night of dreaming, older than the stars.

Yes, God always comes to us in the dark.

And if we consider this, then perhaps we will begin to realize that, indeed, darkness and light to God are both alike, because God’s presence and power and mercy are not dependent upon whether we walk confidently, whether we understand, whether we see clearly, whether we know exactly what to do next or how. God arrives in the night because God is at peace with hiddenness, with the unfolding mystery that God is to us, with the unfolding mystery that we are to God, and so we are invited, also, to make peace with that which is hidden—the reasons and the justifications and the certainties that elude us, and the ways that love endures regardless of what we know or do not know.

And God arrives in the night because, in truth, the darkness has its own particular knowing—its own intimacies and surrenders and quietude that come precisely when we cannot see everything, when we let go, when we cannot strive or plan or rely on ourselves as much as we do in the light of day.

The night engenders a deeper trust, if we will let it. If we will rest in it.

So whatever you carry with you on this night—a weariness, a fear, a grief, a bitterness, a question, a regret, a secret dream—what you must know is that God is still present to you in this place, God sees you and knows you, even if you cannot see God’s face, even if you don’t recognize who you have become.

Like a mother cradling her child, or like a lover in the darkness, God sees you, God gazes upon you tenderly, whispering gentle reminders of promises made and kept and renewed, of a covenant, of a bond deeper than eternity—one that will not break, even when we do. And we do sometimes.

But God comes to us in the dark, saying: do not be afraid, and saying, blessed are you who mourn, for I will make my home in the cracks of your shattered heart, and saying your pain will turn into joy—not because pain is holy but because I AM, and I am the one who offers you a joy that is deeper than fear — the joy that is my own self, that same self from before the beginning, a divine darkness bathed in the stillness of eternity and traveling, traveling, across the constellations and the cosmos to be here, right here, to hold you when your eyes are blurred with tears and shadows on this long, long, longest night.

And to tell you that even when it’s not ok, even when you are not ok, you are loved.

…

In a few days, we will celebrate a birth, and we will speak of the Light of the World, and on that day we will be talking, of course, about God. But remember, as we do, and as you go from this place tonight, that the Light of the World is not all that can be said of God. For before the light, God was.

And here, in the night of the earth and, perhaps, in the night of your soul, God has not left you. God is still doing what God always has been doing, in that original, timeless, holy darkness: dreaming, creating, forming, loving. Remembering all the prices you have paid. Remembering the promises God has made. And reminding us of the one thing that is always true, the one thing God will never stop telling us, even in the dark:

I am here. I am here. I am here.