I preached this sermon on Sunday, February 23, 2025 at St. Anne Episcopal Church, West Chester, OH. The lectionary text cited is Genesis 45:3-11, 15 and Luke 6:27-38.

I was heartened during last week’s sermon when our preacher, Baker, confessed that he, too, has a penchant for accumulating books. It helped me feel a little bit better about my own endless accumulation! Though I like to say that am a collector of books, because that sounds so much more elegant than “hoarder of books” or “person who is constructing the leaning Tower of Pisa with books.” No, no, I’m a collector. So it’s fine.

Well, with that in mind, I’ll tell you there is something else I am a collector of—and I have stacks of them, too, squirreled away here and there—and that is old greeting cards. I have a tough time letting go of the cards that I’ve received. Whether it’s those I’ve been given as a priest, or for birthdays, or even the occasional thank you note…every so often I’ll open a drawer or a folder and there they’ll be, little bundles of time and relationship and memory.

And just when I think, oh, I probably don’t need to hold onto these anymore, I’ll open one up and suddenly I am reading about how proud my dad was at my high school graduation, or some half-forgotten in-joke from a long lost college friend, or a Christmas greeting from a beloved parishioner who has since died. And I just slide them all back into the drawer. Really, I suppose I am a collector of heartfelt sentiments, but I am not ashamed of that.

Because we need reminders sometimes, don’t we, of all the things that we have been to other people, and of all that they have been to us. And really, when you think about it, those greeting cards and other such notes are one of the few tangible signs we ever receive that this is indeed the case. They are evidence that we’re not, in fact, just isolated figures navigating the surface of the earth, but that we are of something, that our hearts and our bodies have been tethered to something, to someone. And in a lonely age, any such reminder is a precious, even sacred thing.

Think about it: when we die, if a stranger were to go through our house and clear out most of our belongings—the clothes and the pots & pans and yes, even the books—it is only a few items, maybe just the greeting cards and the letters and the photos—that would actually tell the story of the love that has shaped our lives. Sobering thought, maybe, but clarifying, too, about what actually matters in this life. What is worth holding onto and what is worth saying to one another in the bit of time we are given.

And for me, few scenes in Scripture capture the preciousness and power of what is said to one another more so than this morning’s Old Testament reading. To set the scene, we are with a handful of isolated figures navigating the face of the earth—the elder brothers of Joseph, who have come to Egypt in the midst of a famine searching for food. Instead, they end up finding Joseph himself, whom they secretly sold into slavery many years before. Joseph is now a powerful figure in Pharaoh’s household, and at first the brothers don’t recognize him.

But as we hear today, Joseph reveals his identity to them and, instead of exacting righteous revenge or punishment, he does something quite astounding. He pours out words of love. He forgives them and welcomes them and weeps upon them, and what he says is tender and generous and full of unexpected grace.

I’ll admit, sentimental as I am, Joseph’s decision here can still sound a bit unrealistic, the stuff of greeting card verses rather than real life. And that’s fair enough. Accountability for harm done is a real and important facet of healthy relationships, and there are plenty of examples of it in Scripture, too.

But what we might want to take away from this story is not simply that Joseph was a very nice person who did a very nice thing by letting his brothers off the hook, but that this narrative represents something deeper and more profound for the people who wrote it down. It captures something of Israel’s own fundamental, fragile hopes.

They, too, often felt like people isolated on the face of the earth, and like those elder brothers consumed by hunger and regret, Israel prayed that they might one day hear God again saying to them: “come down to me, do not delay…you shall settle in the land…and you shall be near me, you and your children and your children’s children.”

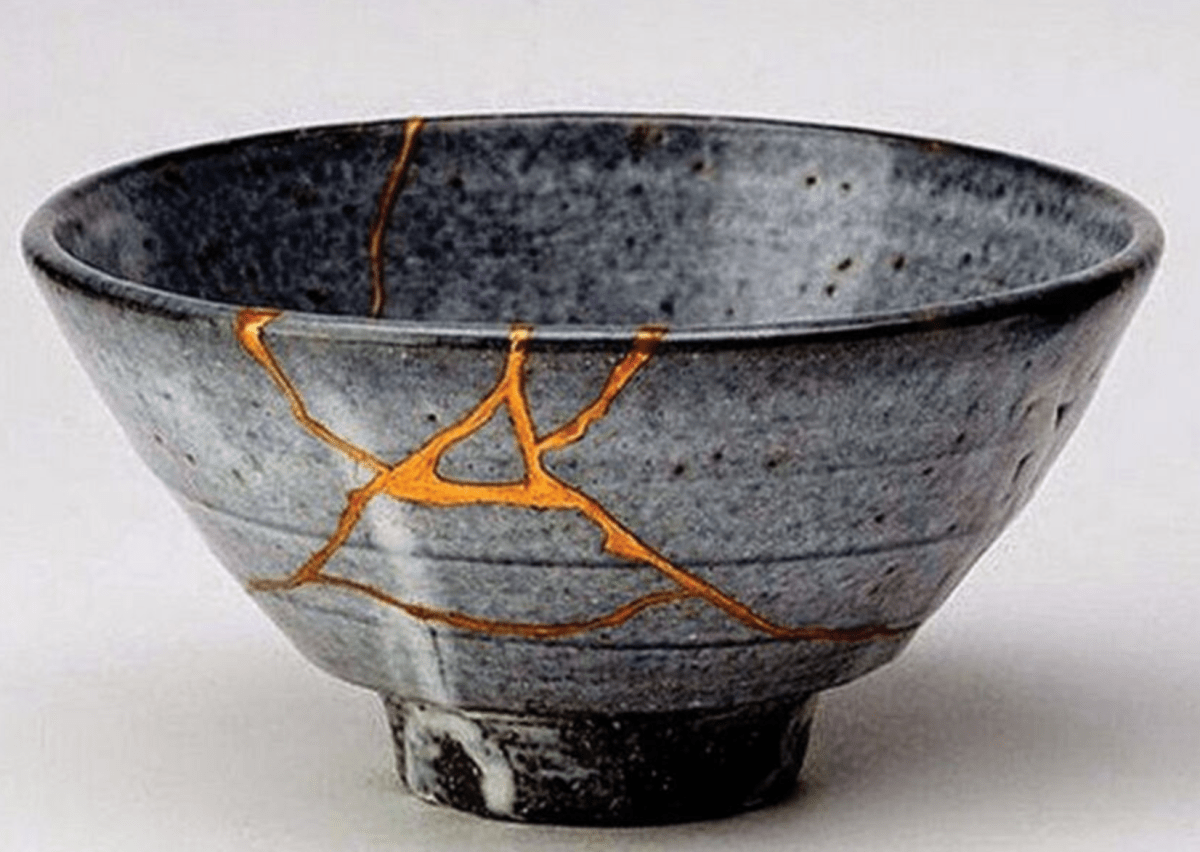

And so what Joseph offers his brothers is what Israel itself longed to receive, and maybe what we all long to receive at our core—a word, an assurance, direct from God’s own heart, that says, “you are not an isolated figure, because you are mine, and I am yours and I, the one who Created you, weep for the love of you. And so no matter what has happened before, no matter what is broken, I your God will make it all fit together somehow. No matter how you have failed, no matter how far you’ve wandered, we are not lost to one another.”

This is not just sentimentality, but the reality of grace. And I think we wait our whole lives hoping to hear some version of it. It is why Jesus came as God Incarnate, to deliver the same message in person through his life, death, and resurrection.

But there’s a twist with Jesus, of course (there always is)—because he invites us not just to receive the word of grace, but to live it. Jesus asks us to become the very word we long for.

And that’s important to keep in mind when we hear Jesus’ seemingly impossible instruction on forgiveness and loving our enemies. Just as we might be incredulous at Joseph, so we might find ourselves skeptical of this teaching. Doesn’t Christ, of all people, know that the world is not so simple? How can we turn the other cheek and resist judgment, when there is so much hate and harm?

And Jesus looks at us and says, because that is what God does. And I, your Lord, have come for one thing: to invite you to participate in the life of God.

And in that Life, God weeps for the love of you. God forgives you. God turns the other cheek to you. God refuses to give up on relationship with you, with anyone. And so if you would dare surrender to the fullness of the life of God…then so it will be for you. For all of us. For at last, in Christ, we will see as God sees and we will love as God loves.

You might even say we will become the people that our stacks of greeting cards say we are–that all of those thank you notes and letters of apology and kind greetings are what will endure of us, once everything else is stripped away.

To become the words we long to hear: this is, at its heart, what discipleship is. Like Joseph and Jesus before us, this is our participation in the life of God. It is God’s sentimental, foolish, stubborn, unabashed, greeting-card-worthy love, now pouring out of us. We who are so used to being strategic in our affections, careful in our compassion….Jesus says, no, the Christian life is something else. It is becoming an unashamed collector of heartfelt sentiments. It is stumbling over teetering stacks of forgiveness. It is letting grace accumulate in your desk drawers. It is to die with nothing but little bundles of faithfulness left behind as our legacy. It is the opposite of the way the world works, and that is the entire point.

So with this in mind, I have a proposal for you. It’s rather simple, maybe even silly, but so be it. This week, I propose that you go out and buy a greeting card and send it to someone. Maybe someone in this community you want to acknowledge. Maybe a friend or a family member whom you haven’t talked to in a while. Maybe even to someone you need to forgive,

Whoever it is, send them a card with a little note, saying whatever it is that you need to say. I wonder what would happen if you did.

It might be that years from now, when most of our other things have fallen apart or been given away, that this part of you will endure. It might be that your notes will still be tucked away somewhere, precious and sacred, a reminder that you were tethered to something, to someone for this brief moment while we navigated the face of the earth together. And that somehow, even with all that is broken all around us, we still fit together, and wept upon each other for love, and at last became the words we longed to hear.

Because God knows: that’s the one thing worth holding onto.