I preached this sermon on Sunday, November 5, 2023, the observance of All Saints’ Day at St. Anne Episcopal Church, West Chester, OH. The lectionary texts cited are Revelation 7:9-17 and Matthew 5:1-12.

It’s in storage at the moment, but I am in possession of a rather unusual coffee table that my mom bought years ago. At the time, she was a young woman living in northern California, and one day as she was driving along, she saw a random man just sitting there on the side of the road selling furniture made out of oddly shaped pieces of reclaimed redwood. Apparently this was *totally normal* in the 70s in California, so she stopped to take a look and ended up going home with this particular coffee table, and it’s been handed on and passed down ever since.

Now I will admit, it is not the most useful piece of furniture. Because it is made from an irregularly shaped slab of wood, you can’t really put much on top of it, and the base is a little bit wobbly, and I’ve lost a few cups of coffee off of it and I’ve banged my shins on its jagged edges more than once in the dark, evoking some colorful language on my part.

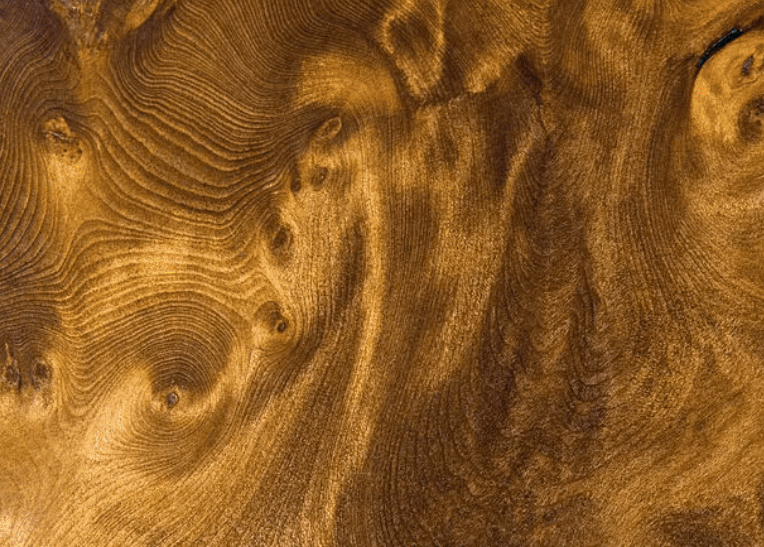

But as impractical as it might be, I will never give up that table. Part of that is sentimentality of course; but also because the wood itself is so beautiful. The man who made it put a protective polish on it, but you can still see the deep, natural, rich hue of the redwood, the undulating grain, the nicks and the scars, the dark glow of its inner luminosity. In all my life, I have never seen another table quite like it. And so someday, when Matt and I have a house, I’ll hopefully find some corner where we can set it up with minimal risk to our shins.

What I love most about that table is that when you look at it, you can see its source. You can see the tree that formed it, the very shape of its origin, the textures and the imperfections acquired by its life in some long forgotten, cloud draped forest. You can see all the things that, when we craft something, are typically glossed over, shaved away, painted and and stained and hidden in the pursuit of a uniform perfection.

And it might sound strange, but I pulled out that table and looked at it this week as I was reflecting on the Feast of All Saints, which we are observing today. All Saints is, itself, a bit of a quirky object with a few jagged edges. One one hand, it’s, of course, a day when we call to mind the saints—people in the distant and recent past who, by some measure, experienced a particular closeness with God and God’s mission in the world. On the other hand, we also incorporate into our observance bits and pieces of All Souls Day, recalling the beloved dead, saintly and otherwise, who have populated our own past and whose memory lingers, sometimes a comfort, sometimes a painful thing we stumble up against in the dark.

And so in this one day we have a whole range of themes, references, and feelings to try and make sense of: a bit of joy; a pang of grief; a sense of calling toward something profound and eternal; and yet a lingering doubt about how to do so when life feels so temporary and fragile.

Our scriptures appointed for the day are similarly confounding. We are given a startling depiction in Revelation of martyrs in blood-white robes before the throne of God, an image that feels both vivid and yet impossibly remote from our day-to-day reality, where blood tends to stain a different color. And we are also given the deceptively simple Beatitudes of Jesus—equally vivid, yet equally remote once we try to figure out how to practically live them out. I have not yet figured out how to determine whether I am sufficiently poor in spirit or pure in heart.

But that confounding quality, that ambiguous, jagged beauty, is, I would argue, the point of this feast, because All Saints, in requiring us to grapple with grief and gratitude and hope all at once, is about reclaiming purpose from those things in our lives that are raw and unstructured and unvarnished, those irregularly shaped experiences we carry with us.

And at its core, All Saints’ wants to teach us that these things are not an obstacle but an answer; that sainthood is not something neat and tidy and peaceful; it is about the courage to reconnect with the deep, untidy, God-given authenticity within us, whether in this life or the next.

Because death and sainthood have something in common: they are both a sort of returning back to God, a stripping away of the cheap veneer, the paint and the pretense. The dead and the saints both experience a reconnection with that mysterious divine power which created all things.

The saints remind us that we can make this return even while we live, that by prayer and service, we can scrub ourselves down to the essential substance of which we were made, revealing the undulating grain, the dark glow of God’s inner luminosity in our very flesh.

But the dead remind us that even if we fail to return to God fully in this life, we will nonetheless, by God’s grace, do so in death, our souls restored to their original character, abiding in God like a stand of redwoods in a clouded forest. Everyone we have ever loved and lost is there now, standing tall and graceful, embedded back into the fabric of life itself, awaiting the day of a new creation when we will be fashioned into something even more honest, more complete.

And so if we read the Scriptures from this vantage point—that sainthood is not about wearing a golden halo but about the reclamation of our raw, inner radiance—then the texts reveal something important, something that my quirky old coffee table also seems to tell me whenever I look at it: our life of faith is not about acquiring layers of lacquer and gilding; it is not about being whittled down into something that barely resembles us; it is not about the straight line or the perfect edge. It is about the surrender to an organic, unbridled sort of beauty; it is about showing forth something of our eternal origins; it is about reminding all who gaze upon us, even with our nicks and our scars and our unsteady legs and our jagged edges, that we bear the image of the One who made us.

Which means that the Beatitudes are not, in fact, a checklist for achieving sainthood: they are the promise that even when bad things happen, even when all else is stripped away from us, our intrinsic blessedness will shine through.

And that image from Revelation is not just a remote tableaux of lofty, saintly figures in white; it is the promise that even when we bleed, even when we die, in Christ we will be revealed as what we always were: vessels of pure, divine light.

So my advice, for all of us, is to let All Saints be what it is. Let it be a little rough around the edges. Let it be delightful and let it be sad. Let it inspire a glance towards heaven and another down towards the dark earth where our loved ones rest. We will say their names and we will sing our songs, and maybe it will all be a little bit wobbly, a bit of a stumbling hazard, but it will be so very honest, so very meaningful, as all real, unvarnished things are.

I know I will never meet that mysterious man on the side of the road who was selling that redwood furniture, but if I could, I think would ask him, what inspired you to try and make something useful out of such rough, unruly, imperfect materials? Didn’t you know it wouldn’t quite work? Didn’t you know we would stumble in the dark and hit our shins and that it would hurt, that we would curse the ground we walk on?

But, at least in my imagination, I wonder if he might look back at me with a dark, gentle glow in his eyes and say,

Blessed are the ones who see the beauty in what is unruly and imperfect.

Blessed are the ones who love such things anyway.

Blessed are the ones who stumble and hurt and keep going.

Blessed are the ones who live.

Blessed are the ones who die.

Blessed are the jagged-edged and the real and the saintly.

And blessed, too, are the ones who simply try.